Editor’s Blog: Was airspace ban necessary?

At first – at least for those outside the aviation industry – the cloud of volcanic ash sweeping across Europe was a novelty. A scarcely believable phenomenon grounding planes across Europe. But as two days turned into three or four, the humour was replaced by bewilderment, scepticism and eventually anger.

What had originally been an entertaining excuse for not returning to work or school after the Easter break quickly became a virtual crisis; as families were separated, transplant organs went undelivered and supermarkets began to question supply chains.

The toll on lost productivity across Europe is still being calculated, but in the short-term the International Air Transport Association (IATA) is warning as many as five mid-sized European airlines are now in imminent danger of collapse following the incident.

So was it really necessary to close all UK airspace for the full six days?

Safety

Naturally safety was the priority as the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) decided volcanic ash posed a danger to civilian aircraft.

Previous incidents had suggested aircraft engines were susceptible to damage from volcanic ash, with commentators pointing to a case in 1982 when a British Airways Boeing 747 – piloted by Eric Moody – had seen all four engines cut out amid an ash cloud over the Indian Ocean.

As data from the Met Office suggested North Atlantic winds would blow ash from Iceland’s Eyjafjallajokull Volcano across Europe, the CAA took the unprecedented decision of declaring all UK airspace hazardous to aviation traffic.

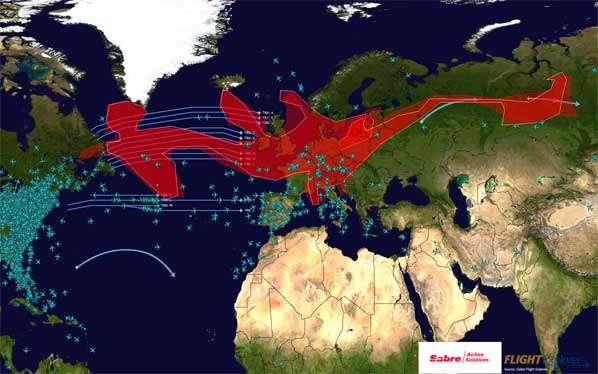

Ash cloud over Europe this morning

In response National Air Traffic Services (NATS) withdrew air traffic controls, effectively closing UK airspace.

“The CAA has drawn together many of the world’s top aviation engineers and experts to find a way to tackle this immense challenge, unknown in the UK and Europe in living memory,” explained the government body.

“Current international procedures recommend avoiding volcano ash at all times.

“We had to ensure, in a situation without precedent, that decisions made were based on a thorough gathering of data and analysis by experts.”

But as the data – and financial losses – began to mount, the CAA’s decision was called into question.

As hundreds of thousands of stranded travellers turned to rail, road and ferry links to make the arduous journey home, airlines began conducting their own experiments to test the CAA hypothesis.

As early as Sunday April 18th – two days after the crisis began - British Airways had dispatched a test flight – a Boeing 747, carrying BA chief executive Willie Walsh – into the ash cloud over the Atlantic Ocean.

Following over two hours of manoeuvres at various altitudes and geographical locations the plane returned to the flag-carrier’s Cardiff maintenance facility where it was examined. Subsequent analysis showed no deterioration in performance as a result of the ash cloud.

This view was supported as major airlines across Europe – including Air France-KLM and Lufthansa – which conducted there own experiments, with similar results.

Air Berlin had carried out three test flights, with chief executive, Joachim Hunold, saying: “We are amazed the results of the test flights done by Lufthansa and Air Berlin have not had any bearing on the decision-making of the air safety authorities.”

So the situation appeared to be stalemated, with the CAA refusing to allow planes to operate in UK airspace, despite claims be the airlines it was safe to do so.

Then the wind changed. On Monday NATS offered a brief hope British airspace would reopen on Tuesday, but later recanted on the plans.

However, this was enough for British Airways.

This volcano continues to spew ash this morning (Photo: Met Office)

Brinkmanship

In the final analysis it may have come down to a piece of brinkmanship from Willie Walsh at British Airways to get the aviation ban lifted across the UK.

As the clouds cleared Mr Walsh ordered 24 BA long-haul departures from around the world to head for London Heathrow - before the official all clear was given.

As these planes approached UK airspace, and with the weight of scientific evidence building, the CAA buckled and changed its advice to NATS.

“Manufacturers have now agreed increased tolerance levels in low ash density areas,” read a statement as airspace was reopened, allowing the situation to begin to return to normal.

Too Slow

But why did this decision take so long?

The IATA argues for a three-day period between April 17th-19, when disruptions were greatest, airlines were losing as much as $400 million per day.

Even a single day of hesitation, therefore, could have been ruinous to one of more regional airline in Europe.

It had taken five days for Europe’s transport ministers to organise a conference call on the issue, while Eurocontrol – Europe’s air traffic control body – appeared to be pulling in different directions from day to day.

The – naturally – unpredictable nature of the weather also played a role, with the MET Office forced to constantly update scenarios for what may, or may not, happen over the coming days. This forced air traffic controllers to make piecemeal decisions; covering mere hours at a time.

In the end it appears an overly cautious CAA was too slow to response to data presented by European airlines.

But, given the vested interests in play, who can blame them?

Chris O’Toole